Jammu and Kashmir: a militarised risk zone, a long-standing and unsolvable border conflict?

Blue Helmets monitoring the line of control between India and Pakistan in the Kashmir region for the UNMOGIP mission, United Nations website.

Tensions in the Kashmir region are nothing new. Since 24 January 1949 (United Nations Security Council Resolution 47, UNSC) United Nations (UN) military observers have been deployed in the Kashmir region claimed by the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, under the auspices of a peacekeeping operation (PKO): UNMOGIP (United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan). The main purpose of this UN mission is to monitor the implementation of the ceasefire agreement established following the first Indo-Pakistani War (1947–1948).

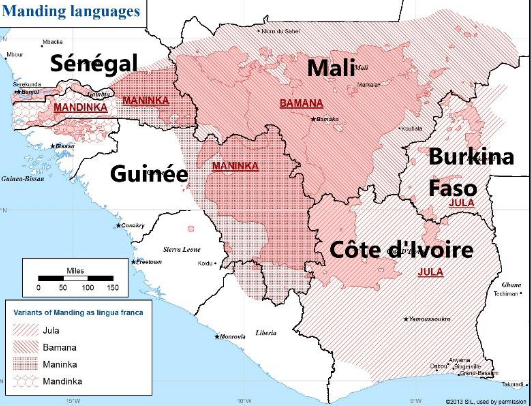

At that time, the British Indian Empire was divided between Pakistan, which was predominantly Muslim, and the Indian Union, which was predominantly Hindu. The princely states of the Empire had the choice between independence and joining either the Indian Union or Pakistan. Only Jammu and Kashmir did not de facto join either state. Clashes then broke out between India and Pakistan to decide who would control the territory. At that point, the UN intervened to propose a ceasefire line, leaving India in control of two-thirds of the area and Pakistan with the rest: this was the Karachi Agreement.

This proposal was accepted by both states, but the referendum planned to make this division official never took place, making the Kashmir region a subject of ongoing disagreement.

Since UNMOGIP came into force in 1949, the UN has also sent numerous observers to the region to report on the situation. This PMF has often been criticised by the recipient states, but has never ceased to be deployed. In 1972, India sought to withdraw its recognition of the OMP, arguing that the Kashmir issue was bilateral and should therefore be resolved solely by the two parties concerned, without the involvement of any third party. Pakistan also criticised the OMP, arguing that it was of little use since it had no means of enforcement if India decided not to respect the ceasefire agreement.

Relations between India and Pakistan remained tense after the UN intervention, with numerous violations of the line of control reported. Mediation attempts between the two countries were made, notably by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which had rather positive results.

However, armed conflicts intensified over time. India continued to demonstrate its superiority over Pakistan with its conventional army. In 1974, the conflicts took a different turn. India launched its first nuclear test, increasing the threat to Pakistan, which continued to develop its nuclear programme in response to India’s advances in this field. In 1998, Pakistan conducted its first tests, following which Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif made a statement justifying his move to nuclear power in order to ‘restore the nuclear balance’ with India. He also declared, “Our decision to exercise the nuclear option has been taken in the interest of national self-defence. These weapons are to deter aggression, whether nuclear or conventional” (1). Without saying so explicitly, Pakistan declared that it could be the first to use nuclear weapons, even in response to a conventional threat from the Republic of India (2). The latter has opted for a policy of no first use of nuclear weapons, like the People’s Republic of China, for example, meaning that it affirms that it will only use nuclear weapons in response to attacks of the same type.

Thus, tensions between India and Pakistan are not easing, but rather intensifying with the nuclear threat hanging over both countries, particularly as neither country is a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT of 1968), raising the possibility of an arms race. Numerous arrests are then made on both sides of the line of control in Kashmir in order to prevent any risk of espionage by the other country, which led to numerous human rights violations against minorities living on both sides of the border and were often the subject of discussions and reports within the United Nations. Recently (3), a Pakistani pigeon entered Indian airspace with a message tied to its leg. It was arrested and the message was examined. It turned out to be nothing more than its owner’s telephone number, but the incident was taken seriously because a few years earlier, another pigeon had also entered India carrying threats against the Prime Minister.

However, despite all the existing tensions, diplomatic relations resumed when the two countries signed the Tashkent Declaration in 1966, ending the second Indo-Pakistani war and re-establishing diplomatic relations. India and Pakistan believe that the Kashmir issue should not prevent other common conflicts from being resolved. Cooperation also emerged following the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States, as Jammu and Kashmir was considered a potential safe haven for terrorists.

However, these good intentions are hampered by events that remind us of the rivalry between these two states. The situation has not improved with the revocation of Indian Kashmir’s autonomy. On 5 August 2019, a presidential decree repealed Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which dated back to 1947 and attached Jammu and Kashmir to India.

With this decision, India provided a legal basis for the occupation of this territory, but granted it a high degree of autonomy. Jammu and Kashmir made its own administrative decisions, with the Indian government legislating only in the areas of defence, foreign affairs and communications. However, following the constitutional reform of 5 August 2019, it is no longer a federal state but has become a union territory, and has been split into two parts: Jammu and Kashmir on the one hand, and the Ladakh region on the other. The aim of this (unacknowledged) manoeuvre is to ensure that the Muslim majority who lived in this federal state become a minority in the Indian Union as a whole, as the government wishes to isolate this section of the population. Soldiers have been sent in to prevent any risk of rebellion and communication systems have been cut off. In addition, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s policy facilitates the settlement of Indians in this area, with Muslims in high-ranking positions being replaced by Hindus. This decision has led to a kind of ‘colonisation’ of the territory by Hindus in order to become the majority in this area.

According to the Indian authorities, the aim of this military annexation of the territory is to bring about peace and stability, but to achieve this end, the Indian government is implementing a system of terror based on the violent repression of Kashmiri opponents.

China, a major player in the Kashmir crisis

This region therefore poses border problems between India and Pakistan, but also between India and China, as Ladakh is located near Aksai Chin, the Chinese territory of Kashmir. As a result, Ladakh is claimed by India but controlled de facto by China. This region is an area of conflict between China and India due to territorial claims. In addition to Ladakh, India wants to gain control over Aksai Chin, as evidenced by Indian maps that include this region in the national territory and are building infrastructure there.

These tensions are not new either. During the British colonisation of India, the British drew the McMahon Line, which was to be the border between India and China in Kashmir. However, this boundary was never recognised by China, and as soon as India gained independence, the Chinese crossed the line and drew a new one corresponding to a ‘line of actual control’. However, this line was crossed on numerous occasions, triggering a border war in 1962 because China had pushed back its border in order to control a larger part of the Himalayan territory. Following this, Indian Prime Minister Narasimha Rao signed a peace agreement recognising the line of control as a de facto border.

Since 2020, tensions have resurfaced and intensified. The Chinese government has decided to increase its forces around the Line of Control and is deploying military personnel and mixed martial arts fighters. In 1996, Narasimha Rao signed an agreement prohibiting the use of firearms in the event of conflict in the region, justifying the deployment of soldiers trained in hand-to-hand combat rather than weapons.

On 5 May 2020, tensions escalated when a Chinese military helicopter flew too close to the border with India, which responded by sending a Sukhoi-30 fighter jet, prompting both sides to reinforce their troops.

On the night of 15 to 16 June, clashes between Indian and Chinese soldiers took place in the Galwan Valley, in the western part of the Sino-Indian border, in the long-disputed Ladakh region. The tensions led to hand-to-hand combat, a violent physical exercise that is very difficult for soldiers, taking place at high altitudes of around 4,500 metres and in temperatures as low as -30°C. These extreme weather conditions cause around 100 deaths per year.

The borders between the two countries are unclear. According to Colonel Dinny, who commanded an Indian battalion in the region until 2017, ‘the maps have not even been exchanged to allow the other side to know what each is claiming. There are no border markers.’ Tensions can quickly escalate if a soldier takes one step too far, thinking they are on their own side of the line of control. The vague demarcation of disputed areas raises the question of who is responsible for initiating clashes. During the events of the night of 15 to 16 June 2020, China stated that it was not responsible, claiming that Indian troops had crossed the border. This had been an issue for some time, as India had begun construction of a road along this line, and with the area being disputed and claimed by both parties, China did not look kindly on this new infrastructure. Observation posts were built along the line of control, but India decided to renege on this agreement and demanded that China do the same. When India’s demands were not met, its army attacked the opposing camp, demolishing the Chinese soldiers’ tents. Following these events, the two foreign ministers agreed to restore the previous agreement and new talks are underway. Since December 2019, negotiation meetings between India and China have been taking place, but none have resulted in a lasting agreement.

In parallel with these peace negotiations, India is strengthening its military arsenal in order to match the level of China, which is the most militarily developed country in the region. The Indian government is emphasising its defence policy by increasing spending on equipment purchases, notably the purchase of 36 Rafale fighter jets from France, delivery of which has already begun. In order to modernise its army as much as possible, India is becoming one of the world’s leading arms importers, developing missile systems for the three branches of its armed forces as well as infantry combat ammunition. The country is also adapting to combat conditions in the Himalayas by purchasing Russian fighters to compete with Chinese soldiers who are martial arts specialists. India’s need to strengthen its arsenal is accentuated by the fact that its two enemies appear to be allying against it. China and Pakistan have agreed on the new Silk Roads project, which is to pass through part of Kashmir under Pakistani sovereignty but claimed by India. This new alliance is favourable for Pakistan, which does not necessarily enjoy much support in the Muslim world. When Pakistan requests that the issue of Kashmir be placed on the agenda of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), it is systematically refused. In August 2020, Saudi Arabia asked Pakistan to repay early a £6.2 billion loan taken out in 2018 and also announced a freeze on oil supplies. This reversal of the situation positions Saudi Arabia as a player that is moving closer to India, weakening the support of OIC members.

In addition to all these military issues that are causing tension in the Kashmir region, there is also a commercial dimension. India has launched a trade war against its Chinese neighbour. To date, this has resulted in the boycott of certain Chinese brands, such as Xiaomi, a Chinese mobile phone brand, much of whose production is based in India. Xiaomi continues to sell its products in India, but only those that are entirely manufactured in India. Shops are required to display a notice on their doors stating that the products are locally made, or risk having their premises vandalised. This is due to the Indian people’s mistrust of the Chinese, as they fear that their data could be more easily retrieved and stored by their enemy. This mistrust has led to another measure, which is the ban on certain applications such as TikTok, WeChat and 59 others, as there are suspicions that privacy rules are not being respected and that certain information is being passed on to the Chinese authorities.

But why is there so much interest in this region? What are the issues at stake?

According to Didier Chaudet, a specialist in South-West Asia and Central Asia, Kashmir is the equivalent of ‘South Asian Alsace-Lorraine’. For Nehru, the founder of independent India, Kashmir is necessary for a strong and pluralistic India, as it shows that India is not only a Hindu majority but also includes a Muslim population.

Furthermore, this region is of geopolitical interest, as it provides access to other regions and countries. For example, Aksai Chin is indispensable to China because it is the location of a road connecting Tibet to Xinjiang; without it, Tibet could find itself isolated. Kashmir is also a key location for water management, as it is where the Indus River flows to supply India and Pakistan. The revocation of Kashmir’s independence is an act that could have serious consequences for water sharing. If India were to decide to build a dam on this river, it could lead to Pakistan drying up. Thus, water, especially with the current issues of climate change, is a significant issue in the Indo-Pakistani conflict.

So what can be done to address all these tensions in the region?

Each in turn, the belligerents call for respect for human rights and a de-escalation of tensions in order to avoid war, but nevertheless, both rivals also show that they will not hesitate to take the step that leads to armed conflict. To prevent this catastrophe from happening, some states are attempting to mediate between the two countries, but this role is difficult to assign because the mediating state must not have interests on either side of the border. The UN wishes to take on this role, as it has been doing since January 1949 by sending military observers to ensure the ceasefire in the Jammu and Kashmir region. Within the United Nations, questions about the Kashmir region arise frequently: how can this conflict be resolved? What measures should be taken against the two belligerents? Are human rights being respected in this region? This last question is often addressed. Recently, UN rapporteurs requested an investigation by the Indian government into ‘allegations of torture and murder in custody of several Muslim men from Kashmir since January 2019’. The underlying question is whether India is truly the world’s largest democracy, or whether it is only a democracy for Hindus. Although these issues are on the agenda, real progress on the subject is complicated and, for the moment, no lasting solution has been found to stabilise the area. Furthermore, more regional approaches have been attempted but have also failed to provide any lasting solutions, as evidenced by the shooting on 17 September 2020 in Indian Kashmir by anti-riot paramilitary forces.

Peace is still a long way off in this part of the world, but it is becoming increasingly important, especially with China’s entry into the conflict, which only serves to undermine the regional balance in Asia. If a conflict were to break out, it could quickly lead to a world war with the alliance system. Major powers would be involved, notably the United States, which would probably not miss an opportunity to cross this line given its differences with China, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region. The United States would find it all the easier to enter the conflict as it has been allied with India since the Clinton administration, and this cooperation has been renewed under President Trump. Although the two current presidents of these countries are nationalists and put forward the interests of their states, the similarities are striking. Indeed, India and the United States have the same profile: they are both multi-ethnic, nationalist states and major democracies facing the same threat: the rise of China.

It is therefore necessary and urgent to find a lasting solution to ease tensions in this region, lest a large-scale conflict emerge. However, a solution found at the UN seems compromised given that the United States and China are among the five permanent members of the UN Security Council with veto power. A regional resolution should therefore be favoured, as desired by India and Pakistan, but a neutral mediator must still be found to liaise between all these states.

Article written by Baptistine PIGNOL, intern at the AISP/SPIA and the International Peace Academy.

(1) “Our decision to exercise the nuclear option was taken in the interests of national self-defence. These weapons must deter aggression, whether nuclear or conventional.”

(2) “Text of Prime Minister Muhammed Nawaz Sharif at a Press Conference on Pakistan Nuclear Tests,” Islamabad, 28 May 1998; text carried by Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), 29 May. Accessed at http://www.acronym.org.uk/old/archive/sppak2.htm

(3) On 25 May 2020 at the end of Eid celebrations.

Sources

Des alliés naturels ? Les relations Inde-Etats-Unis, de l’administration Clinton à l’ère Trump. https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/notes-de-lifri/asie-visions/allies-naturels-relations-inde- etats-unis-de.

Guillard, Olivier. « Inde-Pakistan : sept décennies de méfiance, de défiance et d’opportunités perdues », Outre-Terre, vol. 54-55, no. 1, 2018, pp. 195-211.

Grare, Frédéric. « Entre démocratie et répression : dix-huit ans de contre-insurrection au Cachemire indien », Critique internationale, vol. 41, no. 4, 2008, pp. 81-96.

La Chine exhorte l’Inde à mettre en oeuvre le consensus pour rétablir la paix dans les zones frontalières. http://french.china.org.cn/china/txt/2020-06/25/content_76202998.htm. Consulté le 7 octobre 2020.

« La guerre sino-indienne aura-t-elle lieu ? » Article19.ma, 13 juillet 2020, http://article19.ma/accueil/archives/132001.

Mathou, Thierry. « L’Himalaya, « nouvelle frontière » de la Chine », Hérodote, vol. 125, no. 2, 2007, pp. 28-50.

« Pourquoi l’Inde et la Chine s’affrontent dans l’Himalaya ». Asialyst, 19 juin 2020, https://asialyst.com/fr/2020/06/19/pourquoi-inde-chine-affrontements-himalaya/.

Racine, Jean-Luc. « Le Cachemire : une géopolitique himalayenne », Hérodote, vol. 107, no. 4, 2002, pp. 17-45.

Ramade, Frédéric. « Le Dessous des cartes, Routes de la soie, le Monopoly de Xi Jinping » (vidéo en ligne) arte.tv, 26/09/2020.

Site des Nations Unies sur les opérations de maintien de la paix, page sur la mission Inde / Pakistan : https://peacekeeping.un.org/fr/mission/unmogip