A pitched battle broke out on the peaks of the Himalayas between Chinese and Indian armed forces in the Galwan Valley on the night of June 15-16th, 2020. Soldiers fought armed with sticks and iron bars for several hours at an altitude of 4,200 meters. The death toll was around 20, and each country responded by sending up to 50,000 soldiers per side to guard its border. The situation appeared to be partially resolved in October 2024 after the conclusion of a disengagement agreement following a meeting between Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi during a BRICS summit.

Between April and May 2025, India and Pakistan experienced their most intense military confrontation since the beginning of the 21st century in the Kashmir region. The escalation was triggered on April 22 by a terrorist attack in Indian Kashmir conducted by an Islamist group accused by India of being supported by Pakistan. India chooses to retaliate by targeting infrastructure in Pakistan, and in response, Indian air bases are bombed until a ceasefire is negotiated with the help of the United States on May 10th. Since their partition in 1947, Kashmir has been de facto divided between India and Pakistan, which has already led to several conflicts during the 20th century.

These two recent clashes have revealed the fragility of stability between border powers in the mountain ranges of Central Asia. They raise the question of the strategic issues that drive local powers to seek control of the Himalayas or Kashmir, to establish a presence in territories far from the sea and often sparsely populated, such as Aksai Chin or Tibet, which has three million inhabitants in the Chinese autonomous region, with less than three inhabitants per square kilometer.

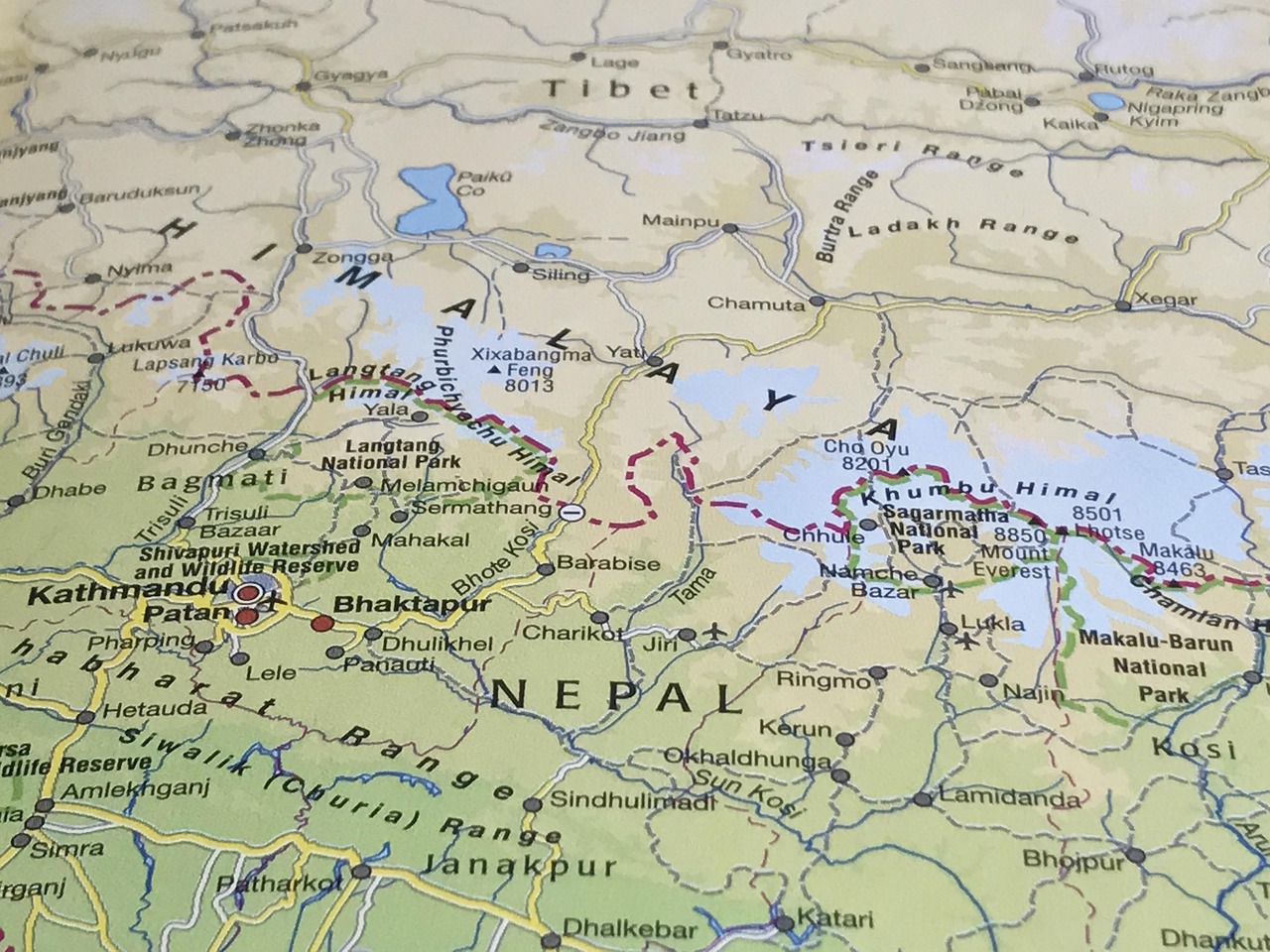

The Himalayas are a 2,400 km mountain range located in Central Asia. They are home to the famous Mount Everest (8,848 meters above sea level), the highest peak on Earth. To the west, the mountains extend into the Pamir, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush ranges. This group of mountains in Central Asia is home to all of the peaks over 8,000 meters, which are renowned challenges for mountaineers, hence its nickname, the roof of the world. Between the Himalayas, Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges lies the disputed region of Kashmir. This area in the heart of Asia is home to three major powers: China, India and Pakistan. In terms of population, China and India are the two most populous countries in the world, with 1.438 billion and 1.411 billion inhabitants respectively. Pakistan follows in fifth place with 242 million inhabitants. They are also military powers, all possessing In terms of population, China and India are the two most populous countries in the world, with 1.438 billion and 1.411 billion inhabitants respectively. Pakistan follows in fifth place with 242 million inhabitants. These countries are also military powers, all possessing nuclear weapons. Finally, in economic terms, China is an economic and industrial power, now stagnating but still predominant on the world stage, while India is showing stronger growth despite its relative backwardness.

Finally, there are also smaller countries in the region, Nepal and Bhutan, which are much less powerful than their neighbors but still retain a certain importance in that they are caught between India and China and can act as areas of competition or separation.

The borders between these different countries have fluctuated throughout history. The border between India and China is partly a colonial legacy, as the two countries are separated in the east by the McMahon Line, established in 1914, originally to mark the border between India and Tibet, which the British had envisaged as a buffer state between the two countries. However, after China’s invasion of Tibet in 1951, the two rivals found themselves facing each other in the heart of the Himalayan mountains. China refuses to recognize the McMahon Line as a legitimate border. In addition, during the 1950s, it gradually took control of Aksai Chin, a region of Kashmir claimed by India under the McMahon Line, thus invading this area already at the center of the disputes between India and Pakistan.

In 1962, a short war broke out between the two countries, which China won militarily. China definitively imposed its control over Aksai Chin. At the other end of the mountains, India retained the region of Arunachal Pradesh, where the conflict also took place, but which was returned to it by China.

Finally, a treaty was signed between the two countries in 1993, with India agreeing to consider the Line of Actual Control (LAC) as the effective demarcation line with its neighbor. However, this agreement did not put an end to the confrontations, although they were not necessarily violent. In 2013, a Chinese patrol settled in an area granted to India under the 1993 treaty, but negotiations proceeded peacefully, despite the proximity of Indian and Chinese patrols. However, in 2020, the violent skirmish mentioned in the introduction broke out, proving that these points of contact between India and China remain areas of tension.

Competition also takes place indirectly within the landlocked countries between China and India. For example, during the Nepalese civil war between 1996 and 2006, China supported the monarchy and India supported the Maoist rebels. China’s expansion is also taking place in Bhutan, where Chinese settlers are establishing villages within Bhutanese borders, a phenomenon that is also occurring in Tibet. In the case of Bhutan, India is concerned about Chinese expansion, and the two countries clashed on the Doklam plateau in 2017. Bhutan is dependent on its neighbor militarily and diplomatically: its army is trained by the Indian army, and a 1949 treaty establishes that it is protected by India and that India “guides” its foreign policy. It cannot stand alone against Chinese incursions and installations and therefore chooses not to respond without India’s support.

The Himalayan range is therefore at the crossroads of several local powers, but also reflects partnerships and rivalries on a larger scale. During the Cold War, the US used its partnership with Pakistan to infiltrate Tibetan independence fighters into China and support their resistance by air. Today, India is an important partner of the United States, which it considers necessary in order to deal with its Chinese and Pakistani neighbors, who appear to be closer. For their part, since their strategic pivot towards the Indo-Pacific, which began under the Obama administration, the United States has sought to limit China’s rise. Since 2007, India has been part of the QUAD (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), a cooperation group with Japan, Australia, and the United States aimed at containing China. Conversely, Pakistan has moved much closer to China to counter the threat from India: China is Pakistan’s leading arms exporter (Pakistan defended itself in 2025 with Chinese aircraft) and the two countries are partners in the construction of economic corridors. This does not prevent Pakistan from being a long-standing partner of the United States (which remained neutral in the 2025 escalation), even if its rapprochement with Beijing complicates this relationship.

In addition, the region has some mineral resources that can be developed. The human presence in certain Himalayan valleys also has more logistical interests: due to its position in the center of Asia, it can be a bridgehead for China’s Belt & Road Initiative (the new Silk Roads) trade routes. The Karakoram Pass is the entry point for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. The Aksai Chin region, under Chinese control, plays an important role in China’s control of Tibet, for example by connecting its western part to Xinjiang in the north. This also involves specific strategies to defend the area, and both countries are investing in infrastructure to supply their defenses: one example is the Sela Tunnel, which India will complete in 2024.

The future of Tibet is also an important geopolitical issue: officially an autonomous region within China, the latter represses opposition there. The historic region has been divided into several provinces and is being colonized by Chinese populations. However, it should be noted that historic Tibet and the Tibetan population are also found outside the territory of the People’s Republic. India has in the past recognized Chinese sovereignty over this territory but is playing an ambiguous game with regard to this region. To begin with, it hosts the Tibetan Central Administration in exile as well as the largest Tibetan diaspora in the world. On the other hand, repression of minorities has intensified under Xi Jinping. China is particularly concerned about the appointment of a new Dalai Lama over whom it would have no control.

The Himalayas and other surrounding mountainous regions are also impacted by climate change, being particularly exposed to glacial erosion and susceptible to the risks of flooding or drought. Pakistan already suffered severe flooding in 2022. However, India’s withdrawal from the water-sharing agreement could prove dangerous if it chooses to influence the flow of water to Pakistan.

Finally, we can mention the issues related to soft power in the Himalayas. China, for example, has appropriated the notion of the “third pole,” notably to justify its interest in the other two, with some maps used by Chinese geographers highlighting the alignment between the Arctic, Himalayas, and Antarctica. China also draws a parallel with its ambition to become a global “third cultural pole.” This term is also used by India and the Tibetan government-in-exile to remind the rest of the world of their presence, as when the Dalai Lama referred to the “third pole” in his speech at COP 26 in Glasgow in 2021. Conversely, China wants to reduce international recognition of Tibet and is therefore seeking to promote the use of the name “Xizang” as a replacement internationally.

In conclusion, the mountain ranges of Central Asia are the scene of ancient and current rivalries linked to military, economic, water, and cultural issues. Sino-Indian competition extends to buffer countries such as Nepal and Bhutan, while Kashmir remains at the heart of the Indo-Pakistani conflict. Resource exploitation, water management, and territorial ambitions are exacerbating tensions. Finally, rivalries are also expressed in the realm of soft power and are exacerbated by climate change. As mentioned in the introduction, China and India reached an agreement in 2024 to peacefully resolve their dispute over their Himalayan border. However, Chinese colonization of the Himalayan territories continues and could cause tensions to resurface in the future. The future of the region will therefore be determined by the ability of the powers involved to maintain the fragile balance that allows them to coexist in the mountains, with or without external mediation from other countries. In addition to the issues raised in this article, there are also national dynamics that may push the leaders of the countries involved toward bellicose or dialogue-oriented behavior, which will also be decisive for the future of the region and the world.

Maxime D.

Bibliography:

Publications:

- Joshi, Manoj. 2022. Understanding the India–China Border. Hurst Publishers.

- S Mahmud Ali, S. Mahmud Ali. 2019. Cold War in the High Himalayas. 1re éd. Routledge.

Journal Articles:

- Alexeeva, Olga V., et Frédéric Lasserre. 2022. « Le concept de troisième pôle : cartes et représentations polaires de la Chine ». Document. Géoconfluences. École normale supérieure de Lyon. ISSN : 2492-7775. octobre 2022. https://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-regionaux/la-chine/articles-scientifiques/troisieme-pole.

- Bhushal, Ramesh. 2015. « First Water Atlas of the Himalayas Launched in Paris ». Dialogue Earth (blog). 11 décembre 2015. https://dialogue.earth/en/water/water-map-himalayas/.

- Da Lage, Olivier. 2025. « Inde – Pakistan : un réel retour à l’apaisement ? » IRIS (blog). 19 mai 2025. https://www.iris-france.org/inde-pakistan-un-reel-retour-a-lapaisement/.

- Pinguet, Laurent. 2018. « Tensions en Himalaya : Toute une montagne ». IRIS, Asia Focus, https://www.iris-france.org/115707-tensions-en-himalaya-toute-une-montagne/.

Press articles:

- Beyer, Cyrille. s. d. « 1962, la guerre sino-indienne à l’origine du conflit actuel | INA ». ina.fr. Consulté le 12 juin 2025. https://www.ina.fr/ina-eclaire-actu/1962-la-guerre-sino-indienne-a-l-origine-du-conflit-actuel.

- Courrier international. 2021. « Village par village, la Chine grignote le territoire du Bhoutan », 13 mai 2021. https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/himalaya-village-par-village-la-chine-grignote-le-territoire-du-bhoutan.

- Dalmais, Matthieu. 2022. « Le Népal et l’Inde s’associent pour de l’Hydroélectrique – energynews ». 18 mai 2022. https://energynews.pro/le-nepal-et-linde-sassocient-pour-de-lhydroelectrique/.

- Landrin, Sophie. 2024. « L’Inde et la Chine poursuivent leur « désengagement » dans l’Himalaya », 1 novembre 2024. https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2024/11/01/l-inde-et-la-chine-poursuivent-leur-desengagement-dans-l-himalaya_6371178_3210.html.

- Mermilliod, Séverine. 2025. « Chine : ce projet de plus grand barrage au monde qui soulève l’inquiétude de l’Inde – L’Express ». 27 janvier 2025. https://www.lexpress.fr/monde/asie/chine-ce-projet-de-plus-grand-barrage-au-monde-qui-souleve-linquietude-de-linde-VIAMBA3UMFHBLCLG3HM3U3NY2M/.

- Thibault, Harold. 2024. « La Chine approuve un projet de barrage géant au Tibet », 27 décembre 2024. https://www.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2024/12/27/la-chine-approuve-un-projet-de-barrage-geant-au-tibet_6469838_3244.html.

Institutional/primary source:

- « The Office of His Holiness The Dalai Lama ». s. d. The 14th Dalai Lama. Consulté le 30 mai 2025. https://www.dalailama.com/news/2021/his-holiness-the-dalai-lamas-message-to-cop26.

- Ligue des Droits de l’Homme : « “Malheureuse maladresse” : le Quai Branly cessera d’utiliser le terme “Xizang” pour parler du Tibet – LDH ». 2024. 3 octobre 2024. https://www.ldh-france.org/malheureuse-maladresse-le-quai-branly-cessera-dutiliser-le-terme-xizang-pour-parler-du-tibet/.