« Peuples et ethnies en Afrique de l’ouest » Peuples du monde et ses minorités

INTRODUCTION

West Africa is a vast region comprising many countries, both developed and developing. Its official area is 6.14 million km2. It includes around ten countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Niger, and Cape Verde. All are the result of colonialism (mainly French and British); their borders, arbitrarily drawn by the former colonizers, determine the current boundaries of these countries.

The era of decolonization in the 1960s fostered the emergence of new states based on a predominantly democratic local policy. To this end, the creation of regional organizations such as the AOF (French West Africa) and ECOWAS reorganized the region around common and promising values (economic, geopolitical, and cultural interests).

The issue of ethnic distribution is paramount in transnational relations. Of Niger-Congolese origin (the sub-Saharan zone from Mauritania to Nigeria), the ethnic groups of West Africa are descended from the majority ethnic groups scattered throughout these African states. These major ethnolinguistic groups (Yoruba, Mandinka, Songhai, Wolof, Hausa, Fulani, Akan, Gbe, Songhai) are subdivided into other families, which are themselves subdivided into subgroups.

Which is the evolution of ethnic groups in West Africa?

–> What is an ethnic group in Africa?

–> How are these ethnic groups spread out?

–> How do they interact with eachother?

–> Looking forward: What if they start asserting their ethnic identities?

I/ GENERAL PRESENTATION

A) Territory: how are these ethnic groups distributed?

Firstly, from a territorial point of view, the distribution of these ethnic groups is based on several criteria. These criteria are historical, political, economic, and environmental. Each major ethnic group has its own characteristics, which stem from an ancient political and social system. The historical and political aspect focuses on the size of empires and primitive principalities before colonization. Maps show that there is a strong ethnic presence in a particular area. In each area, ethno-linguistic groups are distinguished by their traditions, languages, and histories. The great empires and kingdoms 1 lost during the medieval period attest to considerable regional power. The example of the Mali Empire 2 reached its peak under Mansa Musa, making it one of the most prosperous empires in medieval Africa. The territorial remains of this empire have survived to this day (e.g., the Sankoré Mosque); the largest ethnic group is the Mandinka people, depending on the region. This is the largest ethnic group in West Africa, stretching from Senegal to northern Côte d’Ivoire.

One of the characteristics of this region is the spread of precious materials. Each major region has a resource that is conducive to its development. Inherited from the colonial era, the current names of countries and regions reflect their wealth. The Gold Coast region 3 has a strong presence of gold, a precious material closely linked to the Akan people. Generally present in this region, this people glorifies gold, particularly in their traditional ceremonies (e.g., the dowry rite).

At the same time, river areas are also centers of trade and ethnic concentration: on the banks of the Senegal and Gambia rivers, there is a high concentration of Wolofs and Mandingues. In fact, two strong ethnic identities coexist, revealing an accepted cohabitation. These ethnic groups share the same religion: Islam. From a social perspective, caste systems organize the hierarchy of societies. Among the Wolofs, the lowest class corresponds to the descendants of slaves, and the most privileged class is that which occupies positions of authority (“the diambour”). Within the Mandinka community, which is close to the Wolofs, there is a similar hierarchy.

B) DIFFERENT POPULATIONS

i. The Wolof

Among these dominant ethnic groups are the Wolofs 4. This “West Atlantic” ethnic language is spoken by a considerable number of people in sub-Saharan Africa: the Wolof language is spoken by nearly 43% of the population in Dakar, or approximately 4 million speakers in Senegal. Mostly Muslim, they coexist with local minorities and dialects, which are themselves subdivided into subgroups, such as the Serer, Diola, and Halpulaar, representing nearly 40% of the total population in Senegal. In Gambia and Mauritania, they account for nearly 30%, making Senegal the largest Wolof linguistic center. Internationally, the Wolof diaspora contributes to the development of this ethnic group: traditions, culinary practices, and linguistics highlight this ethnic group. The Wolof empire, formerly known as “Senegambia,” included Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania. At the end of the empire 5 and under colonial rule, they settled in the far west off the Atlantic coast and were forced to live within imposed borders.

ii. Mandinka, Malinke, and Songhai

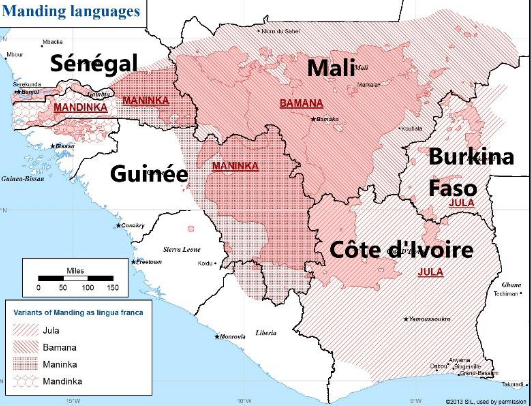

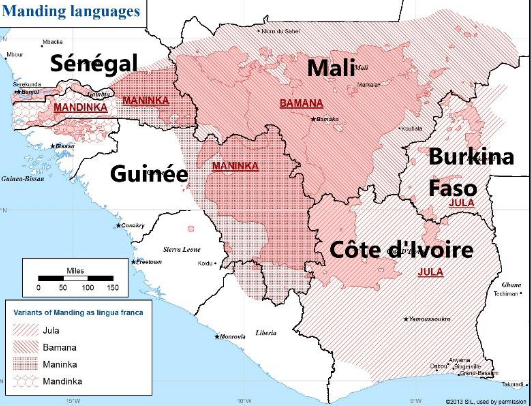

Map of West Africa showing Mandinka influence – INALCO

The Malinkés, Mandés, and Mandikas are all members of the same ethnic group, which represents a majority in West Africa. This ethnic group is present in Mali, Guinea, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Originating in the Mali Empire (the Mandé region) 6, Mandinka is the language spoken in the area. There are several variants of the language depending on the country: Bambara (Mali), Diaoula (Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast), and Malinké (Guinea). In addition, Malinké has had a written language since 1970 (“N’ko”), which enhances the status of this ethnic group on a regional and international scale. This ethnic group relies on song and griots: the most widespread stories are those of the legendary Soundiata Keita and Mansa Moussa, conveying a pastoral identity of the Empire. Locally, the Malinké are respected by other ethnic groups: they are often associated with the descendants of Arabs (“the story of Mansa Moussa”) and generally hold positions of responsibility. In Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire, the strong Dioula presence in high-level positions demonstrates their ability to dominate the political scene.

iii. The Peuls

The Fulani or Fulanis are an interesting people who are constantly evolving. Also part of the Niger-Congo group, they are more or less affiliated with the Afro-Asian group in the same way as the Tuaregs. Nomadism is an integral part of their way of life. They live in several regions, from Senegal to Cameroon. As such, their names change depending on where they live. For example, in Senegal and Mauritania they are called “the Fulani of Fouta Toro” or the Fulani known as “Macina” in Mali. It is understandable that they live in remote plains, rarely coming into contact with local populations. This strategic withdrawal facilitates their development.

iv. Haoussas

The Hausa are a nomadic people who live in several countries in eastern West Africa. They are settled in northern Nigeria, southern Niger, and as far as Lake Chad. Of Sunni Muslim origin, they are herders, farmers, and artisans who live in communities. They are a cross between Afro-Asian origins (Chadic and Niger-Congo languages, like the Fulani). Their area of influence is northern Nigeria, where they are recognized by the Nigerian state. The Hausa language is one of the three official languages after English and Yoruba. This promotes the integration of the Hausa people among the population. The official language recognizes indigenous languages in northern Nigeria as being on an equal footing with English.

v. Yorubas

Pour finir, nous allons nous intéresser à l’un des peuples les plus dominants historiquement, culturellement et politiquement : les Yorubas. Un peuple densément peuplé dans la partie est de l’Afrique Occidentale. Les Yorubas et les Gbês11 vivent une partie au Togo, Bénin et plus particulièrement au Nigéria le berceau de cette branche ethnique. L’empire Yoruba12 a favorisé l’accroissement culturel et politique de ce peuple à travers toute l’Afrique. Le panthéon yoruba repose sur un Dieu suprême le culte de Olorun et inclut, également, d’autres divinités béninoises ou togolaises. On estime qu’environ 50 millions de personnes parlent yorubas à travers le monde.

II/ How do these ethnic groups perceive themselves?

A) Racial and identity perception

From this perspective, questions surrounding race and identity shape individuals from ethnic groups. It is obviously difficult to discuss the causes and consequences of the formation of an ethnic group, especially since it results from several origins. Oral tradition provides many stories that are passed down from generation to generation within families. In many ethnic groups, names and nicknames define the origin or future of individuals from that community.

Onomastic studies assess the importance of names and first names in societies. The name “Sylla” is present in both the Wolof and Mandé ethnic groups and is associated with the upper class—with men of integrity and knowledge, or “Roubasyla” in Malinké. While geographically, the Mandés of Senegal, Gambia, and northwestern Mali are similar to the Wolofs in terms of their names, customs, and cuisine (e.g., the dish Thiéboudienne), the Mandés of Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Mali differ in that their family names have a more local sound. The name ‘Konaté’ 13 (originally from Mali) is often found in Mali and Côte d’Ivoire (in the Dioula subgroup in Côte d’Ivoire). In Mali, the Bambara majority has an esoteric perception, unlike the Malinkés and Dioulas in Côte d’Ivoire, who, for the most part, do not share this view.

Among the Akan people, the Baoulé subgroup considers itself to be descended from a line of dignitaries. In short, the Akan possess symbols of wealth. Gold and ivory are part of their totems. The origin of this Akan subgroup is recounted in a famous story: that of Queen Pokou. Her sacrifice led to the formation of this people. Etymologically, the term Baoulé means “the child is dead” (Baouli).

Tradition is important for spreading knowledge and culture. First, language is a key factor that facilitates exchange: speaking the same language shapes relationships and reduces differences. Linguistically, Wolof is similar to other Niger-Congo dialects. The Wolof and Abbey languages (a dialect and subgroup of Akan) have linguistic similarities. In both languages, the personal pronoun “I” is “man.” This common linguistics attests to their Niger-Congo origin: we can assume a distant origin for Wolof and the Abbey ethnic subgroup.

B) The importance of ethnic tradition

Within this diversity, linguistic expressions convey thoughts and proverbs that illustrate their ways of understanding their histories. A Wolof proverb suggests that “just because I want sauce doesn’t mean I’m going to tip the pot over my head.” This proverb is a self-deprecating joke highlighting patience and discernment in decision-making without rushing. The allegories used perfectly represent African culture. Sauce is a culinary preparation found in most African countries. It is prepared in a “pot,” a container in which the sauce is made.

C) Culture and religion

In this last subsection, we will discuss religious and cultural aspects. Ethnic rites and customs define their identities. The dowry is an essential part of marriage. It is more important than civil marriage. The dowry is a religious marriage: the woman is “offered” to her husband. Before this, the husband must undergo rituals that differ according to ethnicity (e.g., giving a sum of money, making vows). Among nomadic peoples (Fulani, Hausa), the husband may give animals (e.g., oxen) to his in-laws. Synonymous with wealth and offering, this step reassures the husband’s social status with his in-laws.

This practice enhances the status of women. Their status is not inferior, as they also take care of religious matters. For most of these ethnic groups, “spiritual matters” are associated with women. Voodoo is an ancestral religion that is practiced throughout most of Africa. Its religious center is in Benin, extending to Nigeria, Togo, and then to formerly colonized regions (e.g., the West Indies, South America). Beliefs in spirits and totems are common to all ethnic groups, and one ethnic group may worship a religion originating from another. This allows for cultural mixing and mutual tolerance.

III/ Is it possible to live together?

A) Example of ethnic diversity within a country: the case of Côte d’Ivoire

La diversité ethnique est un fait incontestable et réel qui touche toutes les régions du monde. Contrairement aux pays européens, les diversités ethniques au sein des États africains peuvent être un glaive entre la promotion de l’État en question bénie par la diversité culturelle et le risque d’une scission étatique.

The case of Côte d’Ivoire is a poignant example: first of all, the ethnic diversity is real. The birth of this country (March 10, 1893) is based on arbitrary border demarcations resulting from colonization. Originally, it was a region rich in precious materials such as ivory, gold, and cocoa, hence its name. The grouping of diverse and varied ethnic groups is based not on ethnicity but on economic strategy. Currently, there are four major ethnic groups: the Mandé in the northwest (Dioula), the Kru in the southwest, the Gour in the northeast, and the Akan in the southeast. All are subdivided into smaller ethnic groups with their own rites and dialects, which are themselves differentiated by the customs of their villages. For example, among the Akans, the Abbés are a subgroup with the same culture. However, Abbé speakers may come from different villages. Those from the Agboville and Tiassalé regions do not have the same traditions, which is likely to divide this subgroup (e.g., in the case of marriages). In our reasoning, we observe that the country’s major ethnic groups originate from other neighboring countries: the Gours (Senufo and Koulongo) are present in Burkina Faso. The Akans, for their part, have kinship ties with the Ghanaians (the Ashanti subgroup derives from the Akan ethnic group).

This ethnic landscape is characterized by incredible diversity, which in some ways promotes the country’s development. Rituals and celebrations encourage cultural development. The Akans celebrate the yam festival (rainy season and fertility), a tradition that is observed throughout Côte d’Ivoire, not just in one part of the country.

B) Political-ethnic dynamics: what if minorities asserted their ethnic identities?

In this part, we will discuss two studies highlighting the evolution of certain ethnic groups.

❖ Les minorités Sierra Léonaises et Libériennes

Sierra Leone and Liberia are new states composed of local ethnic groups. Founded during the 19th and 20th centuries, they are home to ethnic groups that are predominantly Mandinka. Minorities descended from former slaves have quite diverse origins and are not directly affiliated with any ethnic group. During the major crises of 1990 and 2003, both countries, already fragile, suffered massive population losses. We are seeing migration of ethnic majorities to culturally similar countries (e.g., the Mandinka majority is fleeing to Mali or Guinea Conakry). Let us suppose that after the Ivorian elections in the fall of 2025, the ruling party (e.g., the PDCI) is re-elected. We know that the inclusion of young people in the workforce is a real social issue. Including young people from neighboring countries would stimulate the economy of the host country. In this case, ethnic dynamics should not be considered, only human skills.

❖ The Azawak

The case of the Azawak 19 (northern Mali) is a perfect example of a split within a state. Jihadist influence among the Tuaregs and Fulani 20 encourages communitarianism. In the future, we can imagine the possible independence of this area, where the Tuaregs, Fulani, and nomadic minorities could live. Anticipating the formation of two separate states 21 could benefit the different cohabitations.

In both cases, there is a noticeable initiative on the part of ethnic groups to distinguish themselves. Let us imagine that in 2035, the borders drawn up during colonization disappear. Large ethnolinguistic areas could shape future states: take the example of the large Mandinka ethnic group. The number of speakers spans several regions. In this case, the Mandinka constitute a large ethnic group at the expense of the Wolof or Akan. To this extent, this ethnic group could influence others, particularly through language. Manding soft power would affect the entire western part of Africa as far as Central Africa. Less dominant ethnic groups, such as the Yoruba, could include the Mandinka pantheon in their culture and religion, for example. In short, imagining West Africa without considering the drawing of borders encourages us to take a step back and look at the region as a whole.

Melyss K.

Supervised by Laurent Attar Bayrou, Director of AISP-SPIA

Footnotes

1 Mandinka Empire (12th to 14th centuries). Ghana Empire (6th to 12th centuries). Songhai Empire (15th to 16th centuries). The Kingdom of Dahomey (17th to 19th centuries). These are the main dynasties that had a significant regional influence during the medieval period and into the contemporary world.

2 Founded by the mythical founder Soundiata Keita, the Mandinka Empire reached its peak under Mansa Musa.

3 Ivory Coast and present-day Ghana.

4 Said to date back to the Nile near ancient Egypt. Between Zillofi and Goloff (15th and 28th centuries).

5 The Senegambia Empire in the medieval period.

6 Guinea belonged to the Mali Empire.

7 Emperor of Mali from 1280 to 1337, considered the richest man in history. He restored Africa’s image thanks to his personal wealth.

8 (“pulaaku,” a kind of code of conduct to which all Fulani must adhere). This code includes (“Endurance, wisdom, bravery, Islam, and love of strangers”).

9Four types of people:

Fula of Fouta-Toro (Senegal and Mauritania)

Fula of Fouladou (Senegal, Guinea-Bissau)

Fula of Macina (Mali, Ivory Coast, northern Ghana)

Fulani of Adamaoua (Nigeria, Cameroon)

10 Area located in central Mali in the Ségou region

11 Dialect spoken within local Fon and Beninese communities. Spoken in Togo and Benin 12 The Oyo Empire 1650-1750

13 Ou Keita

14 Queen from Ghana. Legend has it that she sacrificed her son in a river to allow her people to cross. Crocodiles formed a bridge for them to cross.

15 Beggum neex duma taxa deppoo cin lu tàang – Translation into Wolof

16 Women

17 Mandés (Malinkés, Dans, Toura, Gouro, Gagou, Dioula) = Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso

Krus (Wobe, Gueré, Krou, Dida, Bété, Gbadi, Kodia, Bakwe, Neyo, Oubi, Ega) = Liberia

Gour (Senufo, Koulongo) = northern Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso

Akan (Abbey, Baoulé, Akyé) = Ghana Akans

Different AKAN groups = Ashantis and Guangs (Ghana), Baoulés (Côte d’Ivoire), Goumas (Togo)

18 (Abés, Abbey)

19 The “Jews of Africa”? Theory expressed by Amadou Hampate Bâ (1900-1991). Like the Jews, the Fulani have no territory and are scattered: “(communitarianism). Conflicts with sedentary farmers Nomadic herders practice transhumance and “devastate the crops of others.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Bierschenk, T. (1997). Peuples et ethnies de l’Afrique de l’Ouest. Politique africaine, n° 66, pp. 102-114. [En ligne]. Disponible sur : https://www.persee.fr/doc/polaf_0244-7827_1997_num_66_1_6049

2. Voyages Aventures. (s.d.). Peuples du monde et ses minorités : Groupe des langues Nigéro-congolaises. [En ligne]. Disponible sur : https://www.peuplesdumonde.voyagesaventures.com/linguistique/langues-nigerocongolaises/item/544-groupe-des-langues-nigero-congolaises.html

3. INALCO. (s.d.). Fiche Mandingue. Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales. [PDF en ligne]. Disponible sur : https://www.inalco.fr/sites/default/files/asset/document/fiche_mandingue.pdf